Catalina Goanta (17/12/2021). Content Creator/influencer. In Belli, L.; Zingales, N. & Curzi, Y. (Eds.), Glossary of Platform Law and Policy Terms (online). FGV Direito Rio. https://platformglossary.info/content-creator-influencer/.

Authors: Catalina Goanta and Giovanni de Gregorio

During the past ten years, peer-to-peer platforms have democratized and decentralized media services. It is currently possible for any individual around the world to make a social media channel or account (e.g., on YouTube, Instagram, or TikTok) and make content for a living. These developments are facilitated by increased opportunities, from a marketing and technological perspective, to monetize online presence (see also the entry for content/web monetization). Within this framework, a new marketing phenomenon, known as ‘influencer marketing’, has spread online. It consists of a monetization model based on “reviews and endorsements of products online, usually communicated through social networks” (Riefa, Clausen, 2019)1. Outside marketing aspects, the term ‘content creator’ is used to emphasize the fact that social media users take the career path of making media content, especially since controversies surrounding the non-disclosure of advertising or the low levels of diligence exercises by some social media personalities have attracted a negative connotation of the term ‘influencer’ (The Guardian, 2019)2.

‘Content creators’ might therefore be a better term to refer to influencers other than those who engage in influencer marketing as their primary business model. However, it is important to stress that so-called influencers are only a subset of content creators, which is a general term that may be utilized to identify any individual user creating content either for professional or for personal purposes.

Furthermore, it must be noted that defining influencers is no easy task. From a semantic perspective, the Cambridge Dictionary defines influencers as ‘a person who is paid by a company to show and describe its products and services on social media, encouraging other people to buy them’ (Cambridge Dictionary, 2020)3. In a study on social media advertising, the European Commission (2018)4. proposed a similar definition:

a person who has a greater than average reach and impact through word of mouth in a relevant marketplace, and influencer marketing relies on promoting and selling products or services through these individuals

So far, the concept has been integrated into numerous self-regulatory measures around the world, such as the Dutch Advertising Code for Social Media & Influencer Marketing, where influencer marketing is understood to be a marketing activity involving an advertiser and its distributors, in relation to a (paid) communication about a product or brand for the benefit of the advertiser (Art 2(e) Advertising Code for Social Media & Influencer Marketing, 2019)5. The exercise of influence is a core component of these views. According to the Word-of-Mouth Marketing Association6, influence is “the ability to cause or contribute to another person taking action or changing opinion/behavior”. These definitions are built around three common considerations: 1) The existence of a transaction whereby a person is paid to promote something; 2) The person operates on social media; 3) The person has a sphere of influence on which it exercises commercial persuasion.

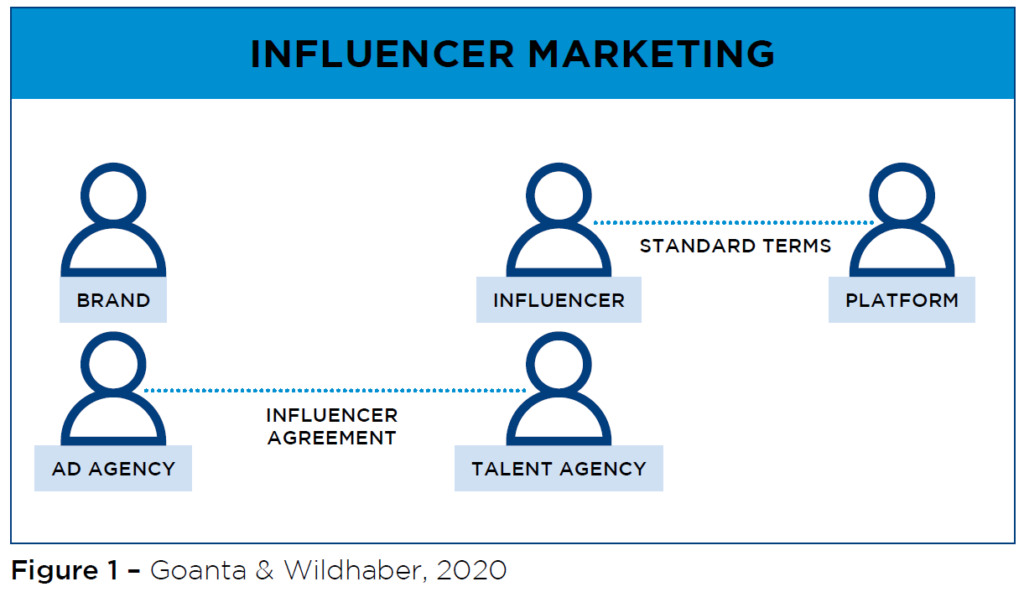

While these features are a reasonable representation of part of the influencer industry, they lead to an incomplete picture on three grounds. First, such features only characterize influencers stricto sensu, namely, to indicate those social media users who engage in influencer marketing as a business model (see Figure 1 below)7.

However, the notion of influencers should be seen from a broader perspective. Influencers come in all sizes and species, and they can range from humans to pets, or even accounts of curated content (e.g., meme accounts such as those used by Michael Bloomberg in his 2020 Instagram campaign ads). At the same time, on the basis of the size of their following, there can be mega-influencers (most renowned creators in a given industry), micro-influencers (rising stars with fewer followers and popularity than mega-influencers), or nano-influencers (small-scale influencers focused on word-of-mouth in more granular communities). Secondly, influencer marketing regards a plethora of monetization models to build their revenue, such as crowdfunding on Patreon, direct selling of own merchandise (‘merch’), or ad revenue through programs such as AdSense or Instagram TV (see also the entry for ‘content/web monetization’). Thirdly, these strategies do not only concern commercial content but also extend to political speech. Influencers do not exercise commercial persuasion connected to commercial transactions but also engage in communications of a different nature than commercial (e.g., political communication). Moreover, with the rise of social justice influencers, influence can also be exercised through e.g., the promotion of social messages and calls for action to support civil society organizations through donations, which is different from promoting goods/services, although the activity itself may be based on similar monetization models as commercial influencers (e.g., ‘endorsement contracts’, De Gregorio, Goanta, 2020)8.

On the basis of these insights, we propose a more all-encompassing definition of an influencer, as the person behind a social media account who creates monetized media content with the goal of exercising commercial or non-commercial persuasion, and that has an impact on a given follower base. From a policy perspective, addressing influencers marketing could affect the right to freedom of expression and, therefore, regulators should take into account the degree of interferences of potential regulatory interventions. Within this framework, consumer law can play a critical role in defining what the boundaries of unfair commercial practices are and to what extent some practices are prone to manipulating consumer behavior or political ideas for commercial gain.

References

- Riefa, C., Clausen, L. (2019). Towards Fairness in Digital Influencers’ Marketing Practices. Journal of European Consumer and Market Law, 64.

- Stokel-Walker, C. (2019). Instagram: Beware of bad influencers. The Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2019/feb/03/instagram-beware-bad-influencers-product-twitter-snapchat-fyre-kendall-jenner-bella-hadid.

- Cambridge Dictionary. (2020). Influencer. Available at: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/influencer.

- European Commission. (2018). Behavioural Study on Advertising and Marketing Practices in Online Social Media. Final Report. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/osm-final-report_en.pdf.

- Reclamecode. 2019. Advertising Code for Social Media & Influencer Marketing. https://www.reclamecode.nl/nrc/reclamecode-social-media-rsm/.

- Word of Mouth Marketing Association – WOMMA. (2017). The WOMMA Guide to Influencer Marketing. Available at: http://getgeeked.tv/wp-content/uploads/uploads/2018/03/WOMMA-The-WOMMA-Guide-to-Influencer-Marketing-2017.compressed.pdf.

- Goanta, C., Wildhaber, I. (2020). Controlling influencer content through contracts: a qualitative empirical study on the Swiss influencer market. In: The Regulation of Social Media Influencers. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- De Gregorio, G., Goanta, C. (2020). The Influencer Republic: Monetizing Political Speech on Social Media.Available at: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3725188.